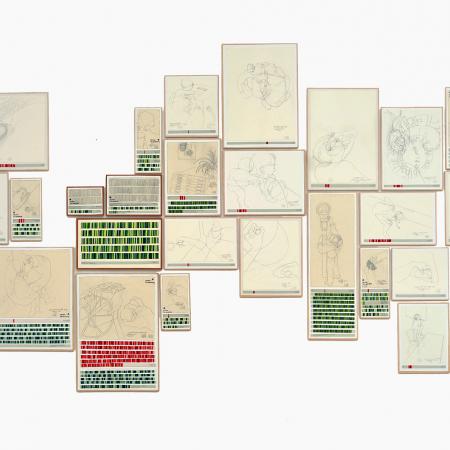

Chiharu Shiota. Earth and blood

Chiharu Shiota, Osaka 1972, presents in this new exhibition a series of works that explores her relationship with nature, and her body. The exhibitions consist in a video installation with six works and a thread installation with a dress, sign for her of a second skin. In her work, Chiharu Shiota uses thread, broken windows, old clothes and shoes… If these objects create a disturbing feeling, they also revive memories of the past that we have been accumulating during years.

Well known for her installations with thread as main material, Chiharu makes them as symbols of what we are and the things we belong to, creating an oppressive atmosphere. Always seen at first sight, her installations locate us in a dreamful place, where we develop a certain state of anxiety.

Trying to get over a miscarriage, the artist went back to work with earth as a basic material.

“With the deadline of the exhibition I thought ‘Do I really have to make Works when I feel like this? But then the title Earth and Blood came to me and I was helplessly overcome by a torrent of sadness anger and anxiety. At the end I show some extremely dark videos and drawings. I wanted to make something that conceal my feelings but I simply couldn’t hide”.